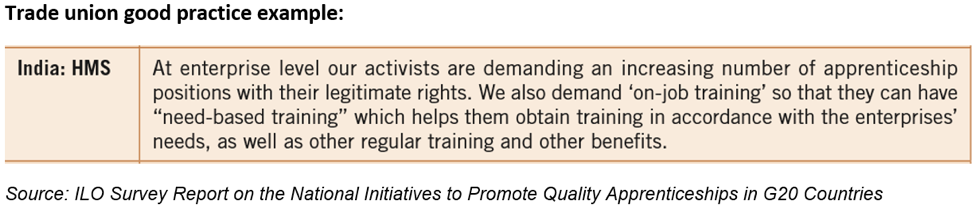

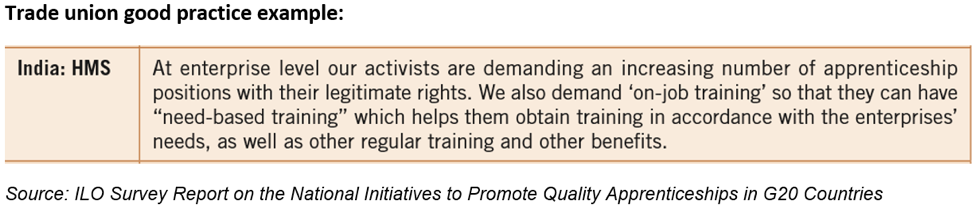

Welcome back to the continuation from Part I and Part II of our series on the above named ILO report.[i] This time we explore findings and good practices of social partners’ actions, namely employer and worker groups. Responses from India were provided by the All India Organisation of Employers (AIOE) and the Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS). AIOE, allied to the FICCI is the apex national employers’ organisation and HMS is a national trade union centre.

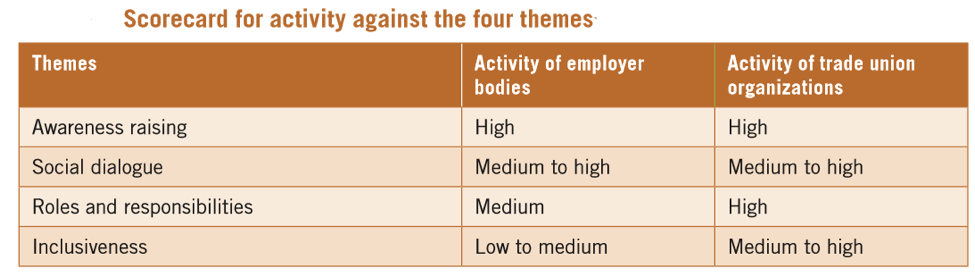

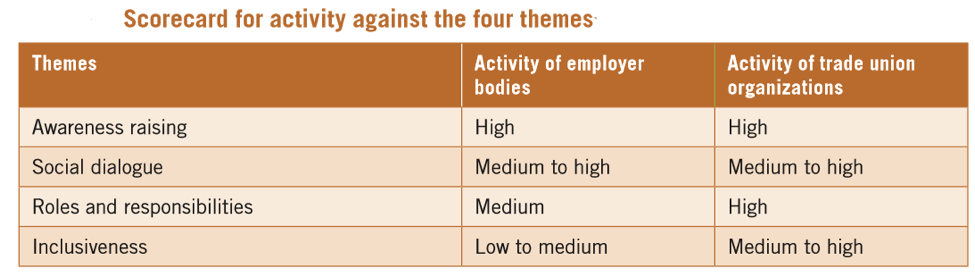

Employer and worker groups are key stakeholders of apprenticeship systems and ideally should be actively involved in the Ten Actions of the G20 Initiative to Promote Quality Apprenticeships discussed in Parts I and II. Responses from individual G20 countries were collated across 4 themes.

Theme 1: Awareness raising

A deficiency in information and awareness around apprenticeships often results in a dual problem of low involvement of businesses in apprenticeships and apathetic youth cynical about the career prospects of skills-based trades. Hearteningly, over 80% of the workers’ and employers’ organisations reported actively raising the profile of apprenticeships among enterprises and youth. All the employers’ organisations cited rallying their members to offer apprenticeship training, with the AIOE specifying capacity-building activities and training workshops for member enterprises to promote apprenticeships.

Similarly, trade unions reported promoting apprenticeships via three main activities:

- Collective bargaining

- Collaborating with other bodies

- Engaging with mentors to support training programmes

Theme 2: Social dialogue

Over 50% of employers’ and workers’ organisations engage with sector skills councils or similar entities, and around three-quarters with other types of national bodies relating to apprenticeships.

However, we find indications of gaps in India in cross-stakeholder social dialogue. To exemplify, dissent was voiced by major trade unions including the HMS recently, against what they felt were non-consultative amendments to the Apprentice Act (1961) which saw an increase on the number of apprentices a firm can employ from 10% of its workforce to 25%. Trade unions believe this move which was taken without proper engagement with workers gives a free hand to employers “to replace regular and contract workers with apprentices with payment of stipend which is less than the minimum wage.”[ii]

From the government’s stand-point raising the cap on the number of apprentices for employers will boost apprenticeship numbers from the dismal 3 lakh apprentices in the country towards a target of around 20 lakhs. However, trade unions perceive the amendment as detrimental to contract labour and apprentices in the absence of basic benefits and worker rights.

Ergo, open communication between representatives of all relevant institutionalised groups and their ability to bring their voices to the table on key decisions around apprenticeships are vital to strengthening national apprenticeships systems.

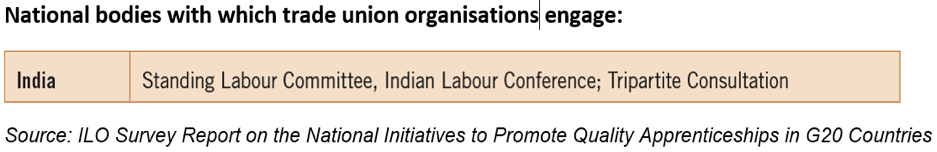

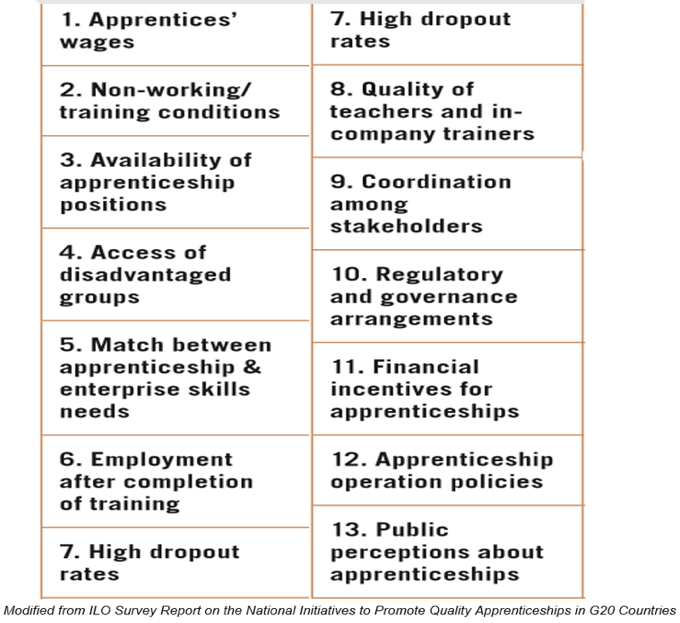

In matters concerning regulations on apprenticeships, the ILO survey similarly found minimum involvement of trade unions with governments of most countries. One exception was Germany, often a poster child of a model apprenticeship system, with the German employers’ organisation reporting close consultation and negotiation with the government on almost all of the 13 specific topics around social dialogue wrapped around three themes- negotiation, consultation and information sharing.

The AIOE responded ‘No’ to each of the above 13 components in the question:

“During the past year, in what ways (i.e. negotiation and agreement, consultation or exchange of information) was your organisation involved in social dialogue at the sectoral/national level with the government or trade unions?”

Reasons for answering in the negative are beyond the scope of this ILO survey. However, conversely and surprisingly, when the same question was put forth to the trade union group HMS, it said ‘Yes’ to being involved in social dialogue with Indian employers, in each of the following components:

- Wages

- Availability of apprentice positions

- Access of disadvantaged groups to apprentices

- Match between applications and enterprise skill needs

- Apprenticeship operation policies

- Public perceptions on apprenticeships

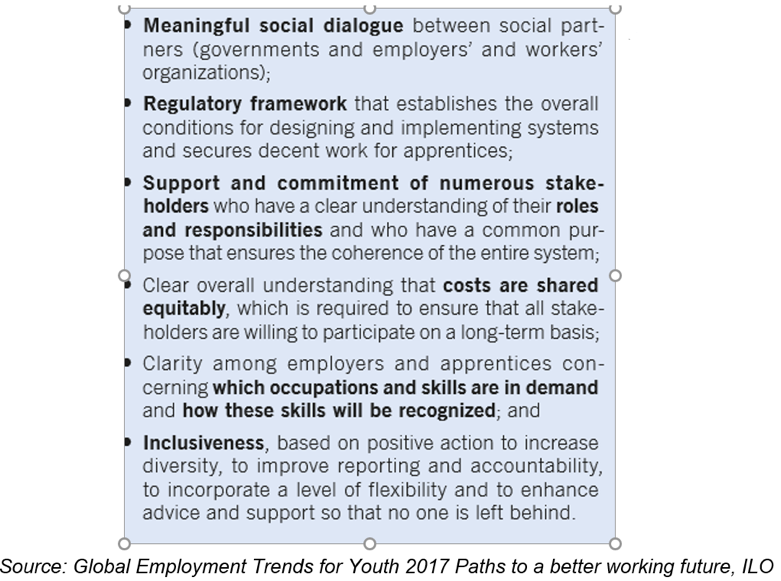

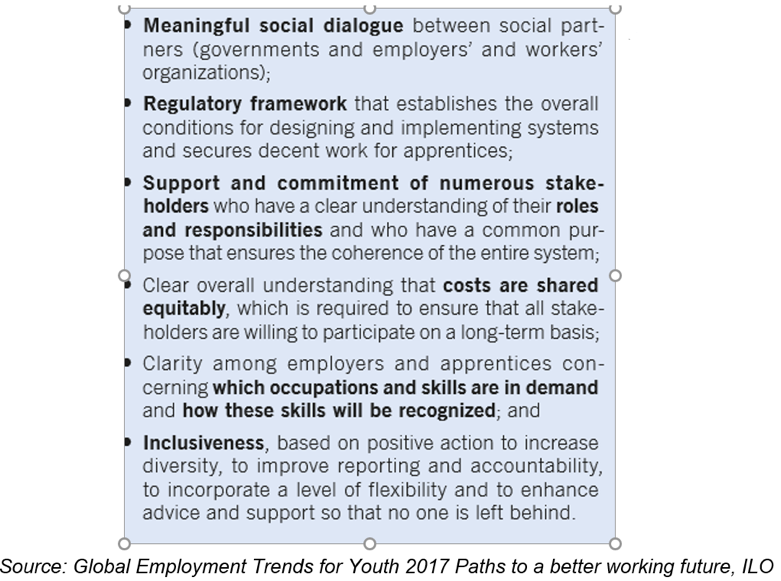

Given their size, the AIOE and the HMS are both highly representative of Indian employers and workers, therefore one could assume, based on the HMS responses, that both groups should have crossed paths at some point in social dialogue engagement around apprenticeships in the year prior to this ILO survey. Or could the stark difference in their responses be indicative of a need for improved coordination and closer participatory working of key stakeholders of the apprenticeship system- a vital pre-requisite for the country to move to terra firma as it seeks to inextricably thread apprenticeships to its Skill India mission. The importance of meaningful social dialogue is also underscored by the ILO in its six building blocks of a quality apprenticeship system- central to which are open communication and a framework of collaborative working.

Stay tuned

In Part IV of this series we will examine the remaining two themes of social partners’ engagement in apprenticeships- namely, roles and responsibilities, and inclusiveness.

References

[i] Main source- ILO Survey Report on the National Initiatives to Promote Quality Apprenticeships in G20 Countries, ILO- JPMorgan Chase Foundation, 2018

[ii] Trade Unions Against Labour Policies- 06 Jan 2019, The Caravan

Dear Nomita, could you pls provide contact details, would like to get in touch regarding Apprenticeship in India