India continues to face steep challenges in meeting its employment targets and lack of employability skills seems to be a key hurdle.

According to the NSSO’s latest jobs survey, albeit controversial, 50 percent of India’s working-age population (15-64 years) is not engaged in any economic activity. Employability comprises of several factors – such as access to education and training, relevant technical or trade skills and core work skills.

What are Core Work Skills?

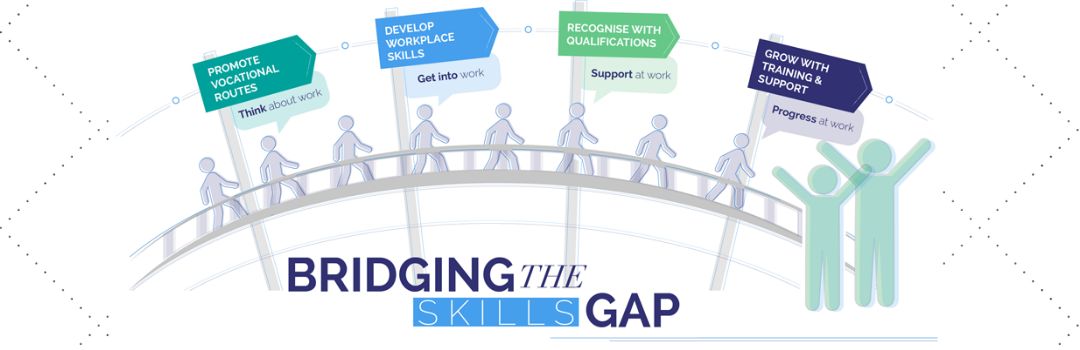

These are employability skills that are built upon basic foundational skills such as reading, writing and numeracy, and which an individual requires to be able to land a job, retain it and advance in their career.

Core work skills as identified by numerous studies are broadly categorised as learning to learn, communication, teamwork and problem-solving.

Specific core work skills have been identified for the Indian labour market.

The Gap

While there exists substantial information on how to address core skills through an education, there is considerably less guidance for policy-makers on how to integrate the same into general education and technical and vocational education & training (TVET) systems.

ILO research states that a complete framework on how core skills can be introduced in skilling systems can be exemplified only through a select sample, after 30 years of international policy-making and deliberations.

Why TVET?

TVET and the skills development route is increasingly being felt as crucial to a country’s employment and employability challenges, a way out for millions of youth to acquire skills and gain meaningful employment. We feel this is partly because a traditional education route simply cannot a) accommodate a heaving mass of youth requiring a quality education every year b) fulfill youth aspirations where traditional education is not desired. Enter TVET, a pathway to provide valuable skills and boost the employability of youth.

We appraise the importance of integrating core work skills into TVET by exploring findings from the ILO report Integrating Core Work Skills into TVET Systems which examines the level of integration of core skills for employability in TVET systems in six countries including India.

Also Read: Effect of TVET on Labour Productivity

Influencing Factors

The implementation of core skills in TVET systems is typically influenced by:

- Historical and institutional contexts such as how much autonomy TVET institutions have in designing a training programme

- The value given to new curricula, guidelines

- Tracking changes in education, training systems

- Tools for assessment of training

- Continuous education and training of trainers and leadership

The UNESCO has found from its review of Asian implementation experiences, a set of characteristics in TVET systems which have been more successful than others in the implementation of core skills:

- Establishing appropriate curriculum goals and standards

- Developing skills in teachers for effective delivery and assessment of core skills

- Thinking outside the box to support innovation and integrate core skills in school practices

- Demonstrating the integration through the implementation of the curricula

- Continuous feedback loop through assessment and evaluation.

Case studies of Core Skills Integration

In this ILO study researchers looked at existing policies to include core work skills into national training systems. The case studies were built on the policy life-cycle approach.

Phase 1- Identifying Core Employability Skills

At the outset it is essential to work with stakeholders to recognise the merit of integrating core skills in TVET by identifying what these core skills are, defining them and prioritising the importance of each core skill. Key stakeholders include relevant government departments, chambers of commerce, trade unions, industry, training providers, trainers, and trainees.

At this stage of the process, it was found that stakeholder involvement in India was mainly on curriculum development; none existed on strategising on the more general need for core skills or their institutionalisation into India’s TVET.

Phase 2- Mapping, revision and/or development of competency standards, curriculum, and resources

Competency-based training in the skills sector in India still requires a lot of polishing, not least due to the absence of a common framework of qualifications encompassing different educational sectors. Yes, there is the National Skills Qualification Framework (NSQF) which has made some inroad since 2013, the National Occupational Standards (NOS) and the Qualification Packs; all with the intent to standardise and harmonise vocational based qualifications. However, a non-existent agreed set of core skills at the national level has resulted in the cobbling together of generic skills in a make-do approach.

Before the existence of the NSQF, NOS and Qualification Packs, the Ministry of Labour established competency-based profiles for core skills under its Modular Employability Skills framework, and these continue to find a place in the Skills Development Initiative short course training scheme. Nonetheless, these standards hold very little meaning outside the remit of the Skills Development Initiative given the disjointed workings of an overabundance of government agencies participating in skills development in India.

Phase 3- Mapping, revision and/or development of delivery, assessment and reporting practices

The Craftsmen Training Scheme and Modular Employable Scheme frameworks in India impart employability skills through detached TVET curriculum modules and related assessment procedures. There is no agreed common framework for core skills, its reporting or assessment threading together the broader skills sector.

Phase 4. Professional development of teachers, trainers and institution managers

The study suggests that teacher assessment and certification should be consistently based on their own skills progression, classroom delivery and impact on student learning. An example of an exclusive core skills training provider for teachers or trainers is Kanumuru Education and Knowledge Ltd where periodic assessments are carried out. Similarly, the National Institutes of Technical Teachers’ Training and Research offer short-term training courses with a focus on core skills.

Phase 5. Awareness-raising/social marketing of core skills among employers, parents, students

In the absence of an agreed core skills framework in India, the only concrete evidence of core skills awareness building was found to be the Wheebox Employability Skills Test (WEST) initiative which involves interviewing students across Indian colleges and subsequent reports based on students testing their skills on the WEST software.

Phase 6. Monitoring and/or impact assessment of the implementation of core skills for employability

This is a particularly weak area in India due to a lack of a formal reporting system of core skills delivery. Stakeholders cited a need for a stand-alone scheme for monitoring and evaluation by an apex body such as the Directorate General of Training, based on international standards. This they feel will raise the profile of core work skills in the minds of students and trainers as a vital component of employability.

Take-Away

The overarching message from this study is that stakeholders feel that policies on skills development are largely silent on the topic of core skills. The closest we have got to is the term ‘employability’ skills which again means different things to different people. There is also evidence of a belief that employability skills are sector-specific which points to a hugely erroneous assumption that a learner will continue in the same sector throughout their career. This tunnel vision results in policy-making wherein there is a push to make youth ‘employable’ by imparting a sector-specific skill. Core work skills, on the contrary, are transferrable skills across sectors which is a key indicator of true employability.

Thus there is a great need to firstly form a nationally agreed definitive set of core work skills for learners and teachers, and integrating the same in both mainstream and vocational education.