Nations with a mature apprenticeship system have in general experienced a smoother transition from school to work and a lower percentage of NEET or a young person who is “Not in Education, Employment, or Training”.

In similar sentiment, in 2014, ILO Director-General Guy Ryder, describing ‘quality apprenticeships’ as the “gold standard”, said, “Countries where apprenticeship systems are strong, youth unemployment rates mirror those for adults. Where apprenticeship systems are weak, youth unemployment is typically much higher, reaching three or even four times the adult unemployment rate.”

Our next topic on ‘Integrating TVET Into Mainstream Education’ continues with the theme of making training systems stronger.

The apprenticeship system in Germany is entrenched in the country’s national fabric of education and training. In December 2016, the unemployment rate for 15-24-year olds in Germany was 6.7% compared with 17.3% across other EU states. The fact that Germany’s vocational training programme which is a substitute to traditional higher education caters to around 60% of the country’s youth has a direct impact on the low unemployment rate in the country.

In India, the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS) has a vision to train 50 lakh apprentices by 2022. Is this an insurmountable task or can it be achieved? We examine the Indian apprenticeship landscape and draw parallels where applicable with other nations with a track record of running effective apprenticeship programmes.

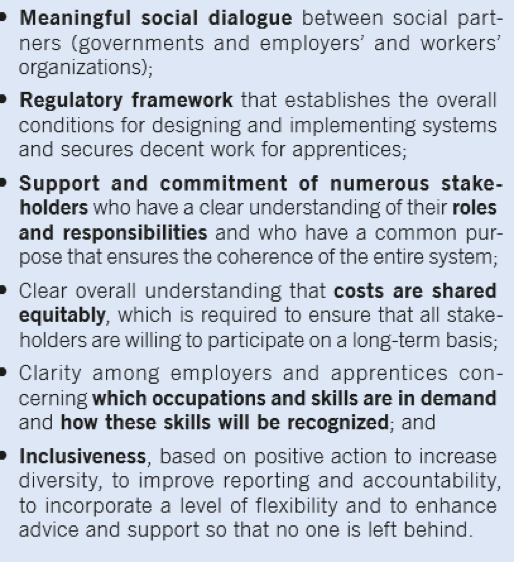

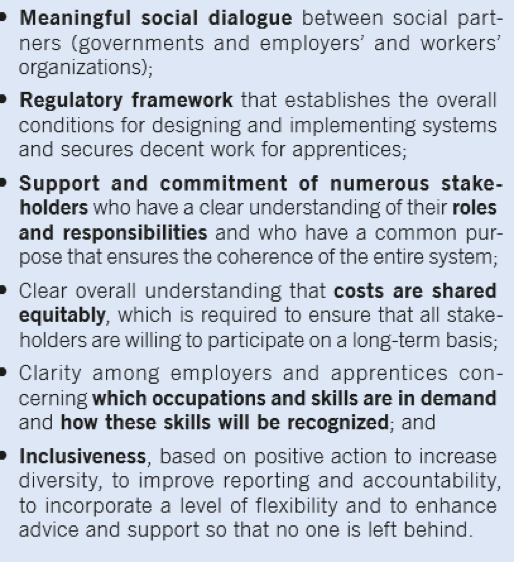

The ILO lists six building blocks for a quality apprenticeship programme. At the heart of it is clarity and a framework of collaborative working.

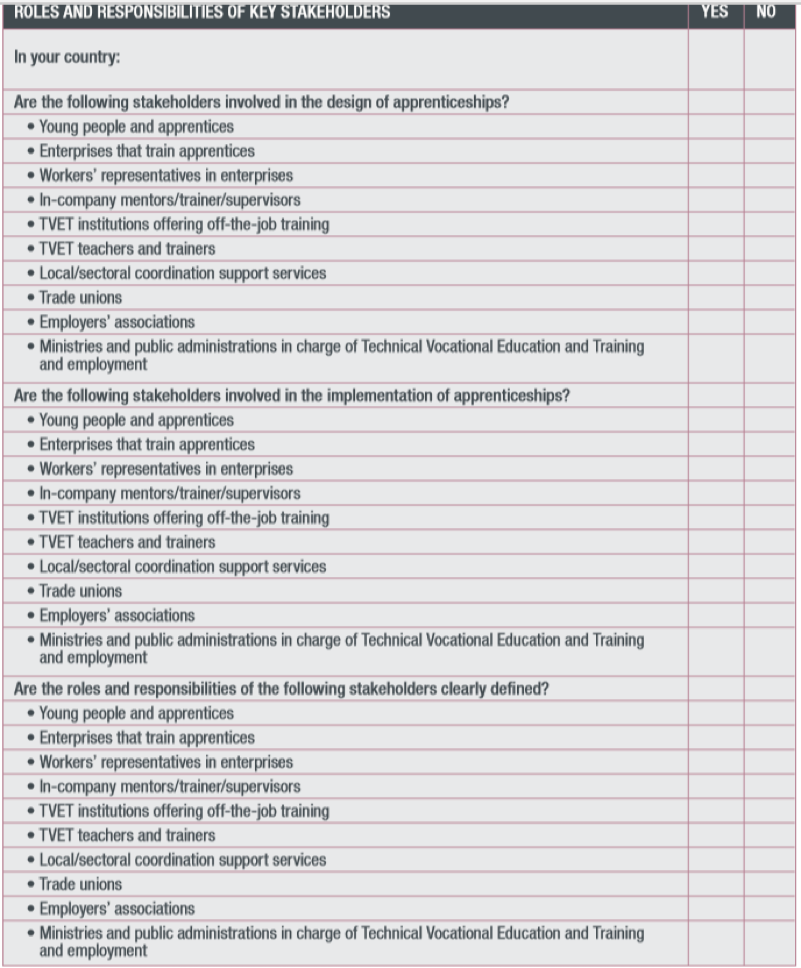

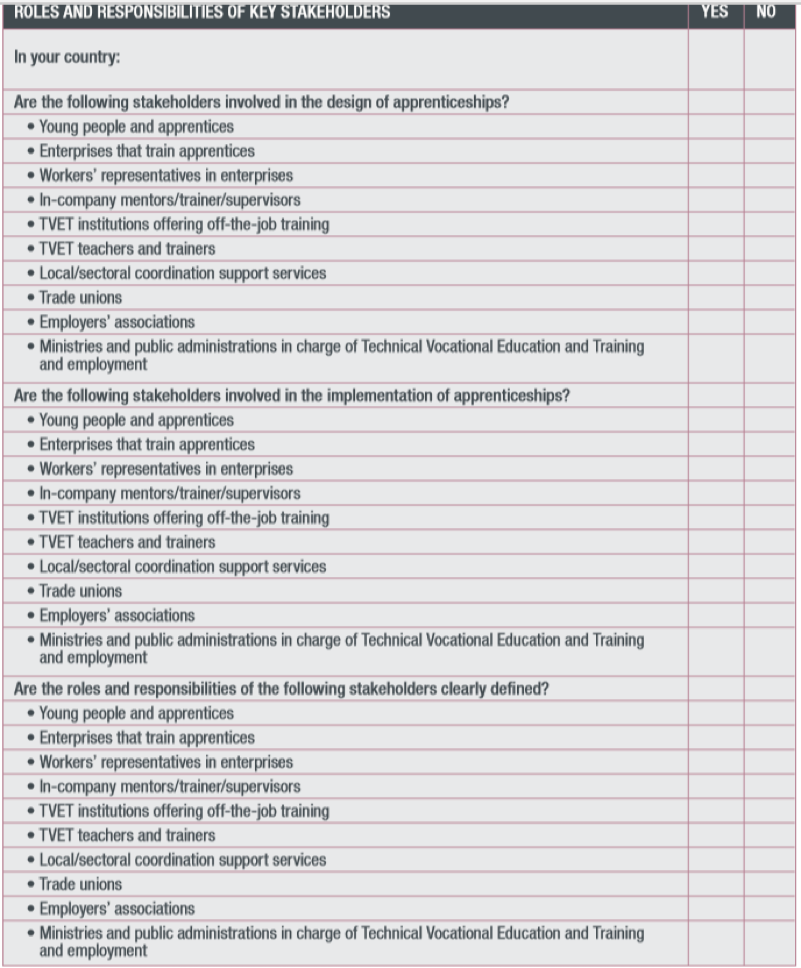

In India, low inclusive participation involving government, industry and civil society has been one of the key reasons why uptake of training and apprenticeships has not gained the required momentum despite an urgent need to skill India’s youth.

The ILO has developed a checklist to assess the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders in a country’s apprenticeship system. If the answer is “NO” to any of the questions, it is advisable to explore ways in which those elements can be strengthened to deliver a more robust ‘quality apprenticeship’ system.

Looking Back to Look Forward

India has a fairly long established apprenticeship training scheme with the advent of the Apprenticeship Act in 1961. However, employers did not take to the Act enthusiastically; it was too focused on the industrial era, there were mandatory requirements to have a fixed number of apprentices every year based on workforce size, punitive penalties including imprisonment for perceived breach of the apprenticeship law, and overall lack of clarity and awareness.

However, starting with industry friendly changes to the Act in 2014, the government’s push towards missions such as Make in India and Skill India are all evident of the good intent towards the ambitious task of turning India into the ‘Skill Capital’ of the world. Other laudable steps in bringing apprenticeships and training to the limelight are the National Apprenticeship Training Scheme (NATS), the National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS), and the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY).

The Scene Today

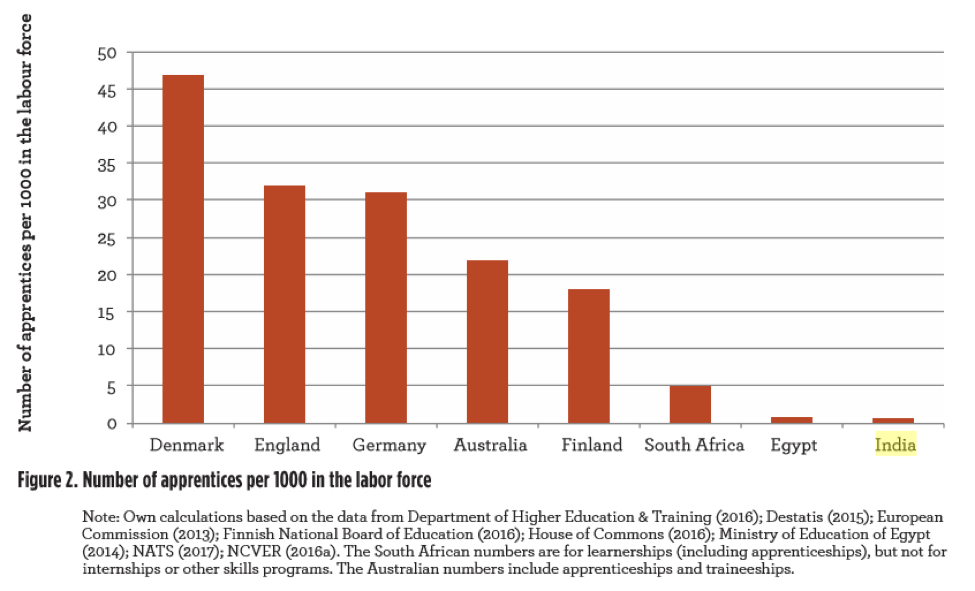

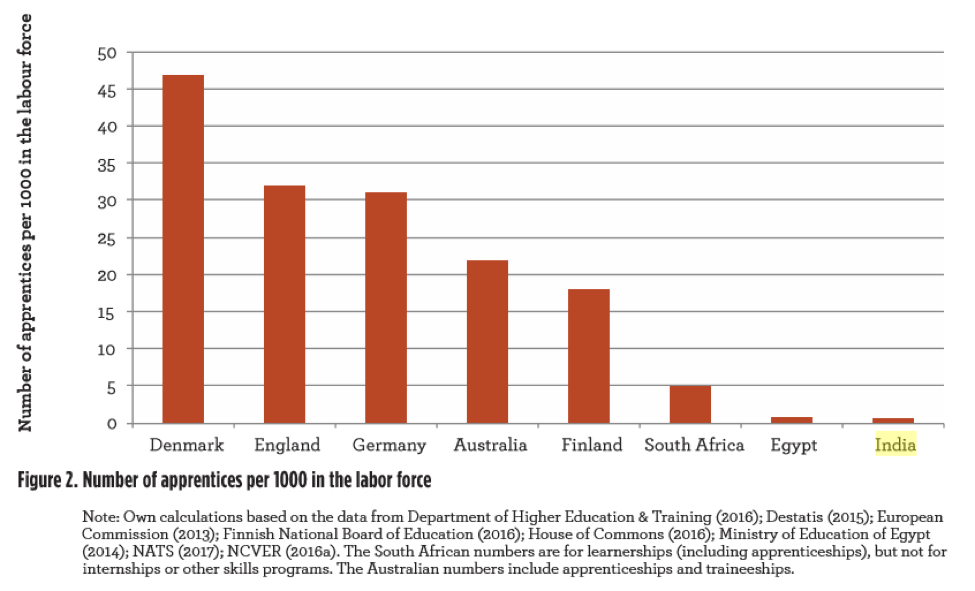

A mere 4.69 percent of India’s workforce is formally skilled,[i] as against 68 percent in the UK, and 75 percent in Germany. The total training capacity in the country is very low, at about 4.3 million for all sectors including manufacturing.[ii] The NATS which should be bridging the gap between education and employment, has suffered from an arduous uptake. The figure below from a major first of its kind study[iii] shows India has a dismal 1 per 1000 apprentices in the labour force. In comparison Denmark has 47 for every 1000.

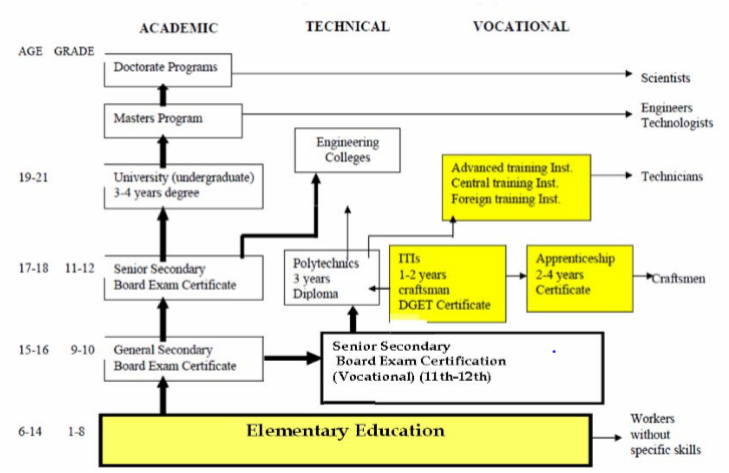

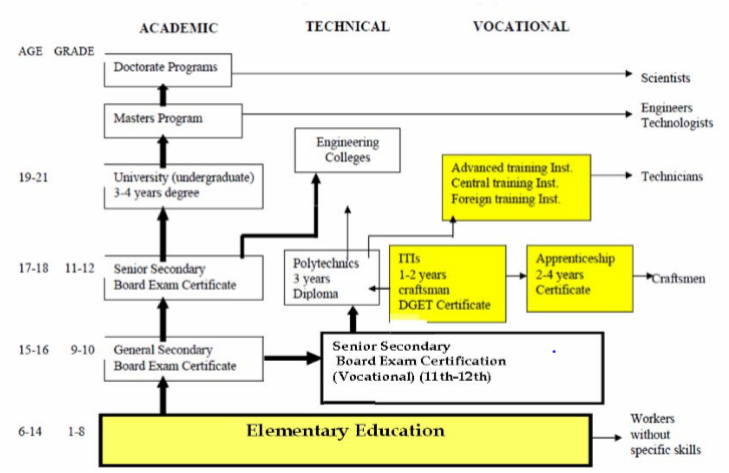

Skills training in India is largely informal i.e. it does not adhere to a particular standard in quality, assessment or qualification. Hence, although the formal apprenticeship and vocational training route exists, such as Trade and Optional Trade, Graduate, Technician and Technician (Vocational), within a fairly well defined framework, the reach and impact of such programmes have been poor. This is notwithstanding the fact that India does have the basic foundation in place for a system capable of being highly effective in the future if the current weaknesses are ironed out.

So what are some of the issues facing training and apprenticeships in India and how can the system become more robust and impactful?

Supply Driven Not Demand Driven

Despite meaning well, the quality of VET and apprenticeship programs in India has been a perennial problem. Obsolete curriculum, low quality training, mismatch of training with industry demand, low private sector participation and low absorption rates by industry have been some of the glaring issues of the VET system in India. However, the government has as of this year transferred in part the running of the NAPS within a public-private partnership mode to the

National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) and the sector skills councils (SSCs) to increase the role of private players. NSDC along with 200+ Indian Leadership Council members plan to flag off apprenticeship training at their corporate premises to boost the NAPS. To further make the system more demand driven solutions such as an app can be used to match employers with job ready youth especially as industry may not know how to access trained youth from various government schemes.

Additionally, curriculum designers have mainly come from government posts chosen on the basis of seniority rather than industry knowledge. This has been one of the key drawbacks leading to irrelevant course content which does little to make youth employable even after undergoing training. Industry experts need to be at the forefront of curriculum development to close the discrepancy between skills demand and supply.

Late Entry Point

One of the biggest stumbling blocks of the Indian apprenticeship and vocational training system is that to participate in it, a young person must have completed at least Grade 8, and in most cases one to three years of formal vocational training at an ITI or ITC. As dropout rate from formal education in India peaks at the secondary level (class IX-X at 17%, as compared to 4% in elementary school)[iv], this is a case of a serious lost opportunity where the young are leaving school with no qualification and no skills. As evident from the diagram below, the ITIs- a major component of the training framework stands outside of the secondary education system- a delink which does very little to capture the young dropping out of formal schooling. A way around would be to lower the entry point to training courses and at lower levels of educational attainment.

Integrating NSQF

The National Skill Qualification Framework (NSQF) was introduced in 2013 with the objective of providing clear progression of skills (from levels 1-10) across a list of trades. A key objective was to make NSQF certification nationally acceptable. However, there exists a gap between the understanding and implementation of NSQF by training providers who should not be viewing the framework as just a series of levels but how each stage requires the participation of different stakeholders such as curriculum developers, trainers, trainees and industry, who are all vital to the success of the framework. Furthermore, NSQF approved Qualification Packs (QPs) and National Occupational Standards (NOS) should be made available to avoid duplication of similar qualifications by different awarding bodies.

Too Many Cooks

Even after the formation of a separate ministry for skilling in 2015 — the Ministry of Skills Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE), skills training is overseen by 17 different ministries in their respective areas – with little coordination among them.[v] This makes it all the more challenging for the MSDE to scale up training through the various kill development missions.

However, a recent step in the right direction has been the merger of the National Council for Vocational Training (NCVT) and National Skill Development Agency (NSDA) leading to the establishment of a single regulator, the new National Council for Vocational Education and Training (NCVET). The NCVET can bring about much needed consolidation to vocational education and training, and remove some of the fragmentation leading to inefficiencies of duplication and lack of coordination.

Mindset Change

In Germany, when companies were asked in a national survey about the importance of in-house training, 63 percent of employers said “because apprenticeship training is a shared task of business and industry and hence a service for society”.

Not all responsibility lies with government and policy makers. Indian industry too has been slow to embrace apprenticeships and vocational training. Countries where skills training is wide reaching, industry participation is high due to a ‘collective good’ perspective. Recent researchiii

has found that when industry decides collectively, as chambers of commerce or associations, or trade bodies, the likelihood of investing time, strategy and funds goes up manifold as the benefits get linked to a common mutual good where skills training is perceived as a contribution to a pool of talent for the entire sector.

In conclusion, a robust training and apprenticeship national system is like a well-oiled machine where each part has its specific purpose and without which the machine fails to deliver. The creation of an all pervasive apprenticeship and vocational education system in a country of India’s size is no minor feat. The blueprint has been laid down and it is the collective responsibility of all stakeholders to help it come to fruition.

References

[i] Annual Report 2016-17, Ministry of Skill Development And Entrepreneurship

[ii] Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012–2017) Planning Commission of India

[iii] People and Policy: A comparative study of apprenticeship across eight national contexts- December 6, 2017, WISE, University of Oxford, Qatar Foundation

[iv] Educational Statistics At a Glance, 2018, Department of School Education & Literacy, MoHRD

[v] India’s skilling challenge: Lessons from UK, Germany’s vocational training models, June 4, 2018